WILLCOX, Arizona, August 17, 2015—Ask Sam Lindsey about

the importance of Northern Cochise Community Hospital and he’ll give you a wry

grin. You might as well be asking the 77-year-old city councilman to choose

between playing pickup basketball—as he still does most Fridays—and being

planted six feet under the Arizona dust.

Lindsey believes he’s above ground, and

still playing point guard down at the Mormon church, because of Northern

Cochise. Last Christmas, he suffered a severe stroke in his home. He survived,

he said, because his wife, Zenita, got him to the hospital within minutes. If

it hadn’t been there, she would have had to drive him 85 miles to Tucson Medical

Center.

There are approximately 2,300 rural

hospitals in the U.S., most of them concentrated in the Midwest and the South.

For a variety of reasons, many of them are struggling to survive.

In the last five years, Congress has sharply reduced spending on Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly, and the patients at rural hospitals tend to be older than those at urban or suburban ones. Rural hospitals in sparsely populated areas see fewer patients but still have to maintain emergency rooms and beds for acute care. They serve many people who are uninsured and can’t afford to pay for the services they receive.

In the last five years, Congress has sharply reduced spending on Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly, and the patients at rural hospitals tend to be older than those at urban or suburban ones. Rural hospitals in sparsely populated areas see fewer patients but still have to maintain emergency rooms and beds for acute care. They serve many people who are uninsured and can’t afford to pay for the services they receive.

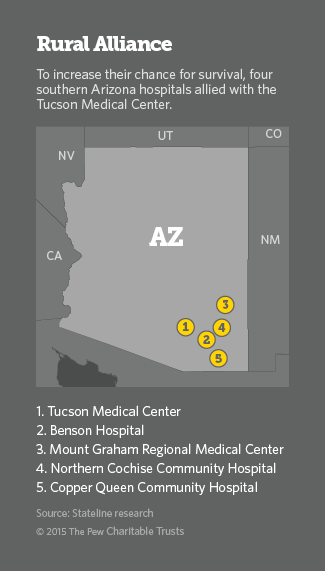

Several months ago, Northern Cochise

sought to strengthen its chances for survival by joining an alliance with

Tucson Medical Center and three other rural hospitals in southwestern Arizona.

Together, the Southern Arizona Hospital Alliance is negotiating better prices

on supplies and services. And the Tucson hospital has promised to help its

rural partners with medical training, information technology and doctor

recruitment.

Several months ago, Northern Cochise

sought to strengthen its chances for survival by joining an alliance with

Tucson Medical Center and three other rural hospitals in southwestern Arizona.

Together, the Southern Arizona Hospital Alliance is negotiating better prices

on supplies and services. And the Tucson hospital has promised to help its

rural partners with medical training, information technology and doctor

recruitment.

“We are committed to remaining

autonomous for as long as we can,” said Jared Wilhelm, director of community

relations at Northern Cochise. “We think this gives us the best leverage to do

so.”

Northern Cochise and the other rural

hospitals in the alliance, which is similar to ones in Kansas, Mississippi,

Washington state and Wisconsin, hope that by joining they will avoid the fate of 56 rural hospitals

that have closed since 2010. Another 283 rural hospitals are in danger of

closing, according to the National Rural Health Association (NRHA).

Right now, some Arizonans in the region

are learning what it’s like to lose a hospital. Cochise Regional Hospital, in

Douglas, near the Mexican border, closed earlier this month, following

Medicare’s decision to terminate payments because of repeated violations of

federal health and safety rules.

The hospital was part of a Chicago-based chain and its closing leaves Arizona residents in the far southeastern portion of the state up to 75 miles away from the closest hospital emergency room.

The hospital was part of a Chicago-based chain and its closing leaves Arizona residents in the far southeastern portion of the state up to 75 miles away from the closest hospital emergency room.

Sam Lindsey shudders to think what a

long drive to Tucson would have meant for him last Christmas.

“If I’d have had to go 85 miles,” he

said, “I don’t think I’d be here today.”

Multiple

Advantages

The alliance offers the rural members

multiple advantages. One of the most important is in purchasing. Their combined

size will enable them to get discounts that are beyond them now.

For example, instead of being a lone, 49-bed hospital with limited bargaining leverage, alliance member Mount Graham Regional Medical Center, in Safford, is suddenly part of a purchasing entity with more than 700 beds.

For example, instead of being a lone, 49-bed hospital with limited bargaining leverage, alliance member Mount Graham Regional Medical Center, in Safford, is suddenly part of a purchasing entity with more than 700 beds.

“If I’m just Mount Graham and I’m going

to buy one MRI every seven years, the sales people will say, ‘Oh, that’s very

nice,’ ” said Keith Bryce, Mount Graham’s chief financial officer. “But as part

of this alliance that they want to do regular business with, they are going to

give us a much better price.”

Bryce said that he expects the added

purchasing power alone will save Mount Graham “in the six figures” every year.

Similarly, the hospitals expect the

combined size of the alliance to result in lower costs for employee benefits,

workers’ compensation and medical malpractice insurance.

The alliance also helps the rural

hospitals recruit doctors and other medical providers, many of whom are

reluctant to work, let alone live, in isolated areas.

Rural hospitals rarely have the contacts and relationships that help urban hospitals find doctors. “We’ve been trying to recruit another primary care doctor to this community for the last year with no success,” said Rich Polheber, CEO of Benson Hospital, another alliance member.

Rural hospitals rarely have the contacts and relationships that help urban hospitals find doctors. “We’ve been trying to recruit another primary care doctor to this community for the last year with no success,” said Rich Polheber, CEO of Benson Hospital, another alliance member.

Tucson Medical Center has pledged to

use its own recruiting muscle to help its rural partners find providers who are

willing to live in rural areas, or at least regularly see patients there. As an

incentive, Tucson will offer interested doctors help in managing the business

aspects of their practices.

The rural alliance members also want

Tucson’s help with medical training and IT. Some have dipped into telemedicine,

which is particularly valuable for rural hospitals underserved by specialists,

and are looking to expand those efforts.

Copper Queen Community Hospital, in Bisbee, the fourth rural member of the alliance and probably the rural hospital in the best financial shape, is the most advanced user of telemedicine. Its networks in cardiology, neurology, pulmonology and radiology can connect doctors and their patients to specialists at major institutions such as the Mayo Clinic and St. Luke’s Medical Center, in Phoenix.

Copper Queen Community Hospital, in Bisbee, the fourth rural member of the alliance and probably the rural hospital in the best financial shape, is the most advanced user of telemedicine. Its networks in cardiology, neurology, pulmonology and radiology can connect doctors and their patients to specialists at major institutions such as the Mayo Clinic and St. Luke’s Medical Center, in Phoenix.

The alliance also will make it easier

for patients who have surgery in Tucson to be transferred back to their home

hospitals for recovery and rehabilitation, saving them and their families from

traveling long distances.

A Defensive

Strategy

Despite the numerous advantages for the

rural partners, the idea for the alliance began with the Tucson hospital, which

approached the others with the proposal last spring. At the outset, some of the

rural hospitals were skeptical.

“At first, we were like, ‘OK, so why

are they doing this? What’s in it for them? Do they want to absorb us?’ ” said

Bryce, the Mount Graham CFO.

But after a series of meetings, the

suspicions disappeared and the rural hospitals eagerly signed on.

The Tucson hospital was frank about its

motivation: to remain independent in an industry moving toward consolidation.

As a result of acquisitions in the last few years, it is the last locally

owned, independent hospital in Tucson.

“All of a sudden, we were in a

situation where [Tucson Medical Center] found itself isolated and facing its

own competitive market pressures because the environment had so dramatically

changed,” said Susan Willis, executive director of market development at the

hospital and president of the new alliance.

Nearly a quarter of Tucson’s patients

come from outside the city, many from the areas served by the rural hospitals

in the new alliance. Cementing the relationship with those hospitals, Willis

said, will help Tucson maintain a flow of patients who need medical services

that are beyond the capabilities of the rural hospitals.

The rural members have laboratories, diagnostic equipment and therapeutic services, but some have little or no surgical or obstetrical services. Not one is equipped to perform complicated surgeries.

The rural members have laboratories, diagnostic equipment and therapeutic services, but some have little or no surgical or obstetrical services. Not one is equipped to perform complicated surgeries.

“Certainly you could describe it as a

defensive strategy,” Willis said.

Decades of

Pressure

Many of the problems plaguing

rural hospitals date to 1983, when Medicare began paying hospitals a set fee

for medical services and procedures rather than reimbursing them for the actual

costs of providing that care.

From 1983 to 1998, 440 rural hospitals closed in the U.S., according to the NRHA. That prompted Medicare to begin reimbursing certain rural hospitals for their actual costs, which helped stabilize them.

From 1983 to 1998, 440 rural hospitals closed in the U.S., according to the NRHA. That prompted Medicare to begin reimbursing certain rural hospitals for their actual costs, which helped stabilize them.

But the recession hit rural hospitals

especially hard, as did 2011 budget cuts that reduced Medicare payments by 2

percent.

Because the rural population tends to be older, rural hospitals rely heavily on Medicare payments. The pressure increased in 2012, when the federal government reduced by 30 to 35 percent its reimbursements to hospitals for Medicare patients who don’t cover their share of the bill.

Because the rural population tends to be older, rural hospitals rely heavily on Medicare payments. The pressure increased in 2012, when the federal government reduced by 30 to 35 percent its reimbursements to hospitals for Medicare patients who don’t cover their share of the bill.

“That’s an example of how a little

policy change that seems insignificant in Washington can have profound effects

in the rural areas,” said Brock Slabach, NHRA’s senior vice president for

member services.

Finally, more insurance plans are increasing copayments and other out-of-pocket costs. Many of the patients at rural hospitals have low incomes. And when they can’t cover their costs, the hospitals have to pick up the tab.

“We don’t have cash reserves,” said Polheber, the Benson Hospital CEO. “We live on the edge, day to day, week to week. [The alliance] seemed like the best way to keep us going.”

Given the threats to the nation’s rural

hospitals, many are eager to learn from any models that work, which is why the

Arizona alliance has attracted notice.

Slabach, for one, calls it a promising

model, although one that may not be replicable everywhere.

“You have to have willing partners willing to collaborate and provide assistance to each other,” he said. “You need partners that share a cultural fit with you.”

“You have to have willing partners willing to collaborate and provide assistance to each other,” he said. “You need partners that share a cultural fit with you.”

The rural members of the alliance are

major employers in their communities and assets in attracting other employers

and residents, including the snowbirds, who flock to the area every winter.

But hospital leaders, workers and patients say saving lives is the main reason the hospitals must remain open.

But hospital leaders, workers and patients say saving lives is the main reason the hospitals must remain open.

“In medicine, distance lessens the

chances of survival,” said Pam Noland, director of nursing at Northern Cochise.

“Even if a patient has to be transferred to [Tucson Medical Center] or

somewhere else, stabilizing them here is the difference between life and

death.”